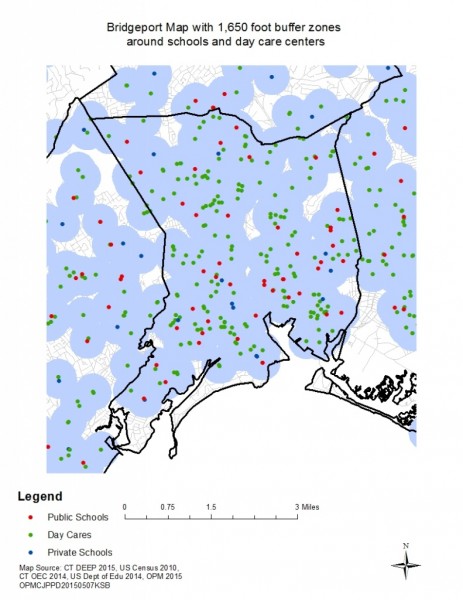

This map of Bridgeport, Connecticut’s most populous city, shows the clustering of school zones where penalties for drug possession and sales are stiffer. Source: State of Connecticut

The chamber’s 151 members were unable to reach a consensus on language in a second chance society bill during the final hours of the legislative session.

But Malloy’s signature criminal justice reform, approved 24 hours earlier by the Senate, could very well be the beneficiary itself of a second chance.

Eight minutes before the scheduled adjournment of the General Assembly, lawmakers adopted an emergency resolution that will reconvene the legislative body for a special session in the coming weeks. An exact date hasn’t been set.

“We will continue to push for it and make it a top priority during the special session,” said Mark Bergman, an adviser and spokesman for Malloy.

The measure, which last month roiled Republicans and ignited claims of race-baiting by the Democratic governor, preserves drug-free zones around public and private schools, as well as day care centers.

The change mirrors a national trend by both blue and red states that attempts to shift police resources to violent crimes and reduce prison overcrowding, while removing mandatory prison sentences for possession of small amounts of illegal drugs regardless of location.

Offenders currently face a two-year minimum sentence for personal possession within 1,500 feet of a school or child care facility, which the bill’s supporters say disproportionately affects black and Latino residents in densely packed cities such as Bridgeport, where 90 percent of the population resides in a school zone.

“Our drug laws punish some communities more than others,” said Rep. William Tong, D-Stamford, co-chairman of the General Assembly’s Judiciary Committee. “When they get out as felons, they continue to face a life sentence, a life sentence in which they can’t get a job, get an education or even find a place to live. These laws contribute to a lifetime of hopelessness and despair.”

The bill is a centerpiece of the second-term agenda of Malloy, who implied that race was a factor in the GOP’s initial resistance to the changes. Three weeks ago, GOP lawmakers walked out the House chamber to protest the racial overtones of Malloy’s comments.

“I was very upset when that occurred, took offense to it, naturally,” said Rep. Richard Smith, R-New Fairfield, who serves on the Judiciary Committee. “This is not about race. This is about fixing an issue that our cities here in Connecticut have been dealing with for quite some time.”

Smith said he appreciated the support of Democratic colleagues who condemned Malloy’s insult and told Republicans, “You’re not a racist.”

The debate over sentencing reforms coincides with soul-searching by Republicans, both in the Legislature and the state party, on urban strategy. The six most populous cities in the state are controlled by Democrats, who have used their urban advantage to sweep every statewide and congressional election since 2008.

During the twists and turns of the legislative process, Malloy found a most unlikely ally in Grover Norquist, the ardent conservative, who penned an opinion piece in the Hartford Courant endorsing Malloy’s plan. The way the law is currently constructed, according to Malloy’s administration, entire cities are effectively school zones.

The bill’s supporters emphasized that the penalties for selling, intent to sell and possession of large quantities of drugs will be unchanged. The state will also continue to mete out harsher sentences for drug dealing arrests in school zones.

To make the legislation palatable on both sides of the aisle, Democratic and Republican caucus leaders tweaked the bill to account for repeat drug offenders and expand the membership of the state Board of Pardons and Parole.

“It was a great moment for all of us to find common ground together and get us to where we are now,” Tong said.

A first conviction for personal possession will be classified as a Class A misdemeanor, which carries a penalty of up to one year in prison and a $2,500 fine. A second conviction would require an offender to undergo a mandatory evaluation for drug addiction that could result in court-ordered drug treatment instead of prosecution. Otherwise, it would be a Class A misdemeanor. A third conviction would trigger a persistent offender statute, which is classified as a Class E felony and carries a penalty of up to three years in prison and a $3,500 fine.

“We’re providing some type of discretion to a judge,” said Rep. Rosa Rebimbas, R-Naugatuck, a ranking member of the Judiciary Committee.